Confiscating assets of the Shining Path terrorist organisation

Confiscating assets of the Shining Path terrorist organisation

This case study details the successful confiscation of nearly USD 1 million from a Swiss bank account linked to Nelly Marion Evans Risco, a former member of the Shining Path terrorist organization in Peru. Evans, known as “The Nun,” was convicted for her collaboration with the group, which was responsible for significant violence and economic damage during Peru’s internal conflict in the 1980s and 1990s. The funds in her Swiss account, initially flagged by the Swiss authorities through a Suspicious Transaction Report, were later seized under Peru’s extinción de dominio law—an autonomous, non-conviction-based asset forfeiture mechanism that allows for the confiscation of assets tied to crime, even in the absence of a criminal conviction. The legal basis for confiscation was the proven intent that these assets were destined to finance terrorist activities.

The Evans case exemplifies the increasing importance of civil asset forfeiture tools in combating transnational crime and recovering illicit proceeds, particularly when traditional criminal convictions are not feasible. It highlights the power of international cooperation—specifically, spontaneous exchanges of financial intelligence—and the advantages of civil standards of proof and partially shifted burdens of proof under Peruvian law. The final court ruling in 2021 confirmed the seizure and ordered repatriation of the assets from Switzerland to Peru. The case serves as a landmark example of how non-conviction based laws can close impunity gaps, recover criminal assets long after original crimes, and restore justice in the wake of historic atrocities.

Section outline

-

March 2021

Confiscating assets of the Shining Path terrorist organisation

Oscar Solórzano

About the author

Oscar Solórzano is head of the Basel Institute's Latin America office in Lima, Peru, and a Senior Asset Recovery Specialist at the International Centre for Asset Recovery (ICAR).

Since joining ICAR in 2012, Oscar has worked on a range of high-profile international corruption and asset recovery cases in Peru and across Latin America. Working with prosecutorial and law enforcement authorities, he helps to develop and execute strategies to trace illicit assets laundered to foreign jurisdictions, including seizing and confiscating the proceeds of the crime.

In particular, he gives advice on the application of non-conviction based confiscation laws as strategies for the international recovery of assets. He also provides legal advice around mutual legal assistance in criminal matters. Oscar regularly represents the Basel Institute as a speaker at international seminars and conferences on anti-money laundering, anti-corruption, international cooperation and asset recovery.

oscar.solorzano@baselgovernance.org

About this publication

This case study was produced in the context of the Cooperation Agreement signed between the Basel Institute on Governance and the Public Prosecutor's Office of Peru.

Its purpose is to provide a documentary record of emblematic cases of asset recovery in which there has been a successful synergy between both institutions. It is a knowledge tool suitable for both a general and specialised audience.

This case study was written by Oscar Solórzano, Senior Asset Recovery Specialist at the Basel Institute on Governance. Its content does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Basel Institute on Governance or the University of Basel.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

Citation: Solórzano, O., 2021. Case study: The Nun - Confiscating assets of the Shining Path terrorist organisation . Basel Institute on Governance. baselgovernance.org/publications/case-study-the-nun

1 Context

At the beginning of the 1980s, the Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso) terrorist organisation led by Abimael Guzmán, also known as Chairman Gonzalo, carried out a violent offensive with the aim of taking political control of the country. According to the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación del Perú - CVR), 1 the victims of this terrible episode, mostly peasants, numbered 69,280. 2 Due to the structural damage it caused, the armed conflict exacerbated existing social inequalities that are still felt today. Apart from seriously 3 disrupting the Peruvian economy, it has been estimated that the Shining Path's activities have caused at least USD 26 billion in property damage. 4

The Shining Path needed funds to operate. However, and despite the fact that the various criminal proceedings against its members had analysed their sources of funding, there are no records of legal actions aimed at recovering assets associated with them. Moreover, as the court decisions point out, doubts remained about the real sources of financing of the terrorist organisation. 5

The case described below reveals a tiny part of the manner in which the Shining Path terrorist organisation was financed. It describes, in broad terms, the prosecutorial strategy that has enabled the confiscation of funds held in one of the organisation's bank accounts. In this context, it also discusses some of the characteristics of the Peruvian law on non-conviction based asset confiscation.

2 Background to the Evans case

Nelly Marion Evans Risco (hereinafter Evans) was a Peruvian-British Catholic nun from Lima's wealthy class. Picking up on her religious role, the media at the time nicknamed her 'The Nun'. According to the CVR report, Evans was recruited by the Shining Path at the beginning of the 1980s, when she was working as a volunteer teacher in one of the most disadvantaged districts of Lima. Gradually, Evans became a key player in recruiting other young militants. The Peruvian judicial authorities maintained that she participated in and provided logistical support to the Shining Path terrorist group. 6

According to the CVR, Evans had used her family fortune to finance Shining Path. However, this

fact could never be proven in court. Evans was primarily convicted for her affiliation to Shining Path and for acting as a front woman for the terrorist organisation. 7

Evans was sentenced to life imprisonment in a 'faceless' military tribunal. 8 When the country returned to normality, the decisions of these tribunals were declared null and void by the Constitutional Court in 2003. Evans received a regular trial with the corresponding judicial 9 guarantees and in 2006 was sentenced to 15 years of imprisonment. However, the judge took into account the fact that she had already been held in detention for a period of 15 years and ordered her immediate release.

In 1991, Peruvian media reported about the existence of a Swiss bank account linked to Evans. 10 In 2017 and 2018, the Swiss authorities spontaneously transmitted more detailed information on account No. 972362 of the Edmond de Rothschild S.A. bank in Geneva ('the Evans account'). In summary, the spontaneous information revealed the following:

- On 20 August 1990, Evans opened the account with a contribution of USD 460,000 from the First Interstate International Bank of Miami.

- Evans is the holder and financial beneficiary of the account.

- On 29 May 2017, Edmond de Rothschild S.A. bank sent a Suspicious Transaction Report (STR) to the Swiss Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU). The FIU reported the suspicious facts to the Swiss Federal Prosecutor's Office, which in September 2017 ordered the seizure of the concerned bank account and the opening of criminal proceedings.

- The account is seized in Switzerland under a criminal organisation investigation (Art. 260 ter of the Swiss Criminal Code).

- On 22 January 2018, the Evans account held a balance of USD 923,736.

The spontaneous transmission of information by the Swiss authorities to Peru was clearly intended to invite the Peruvian authorities to initiate domestic proceedings with a view to confiscating and recovering the assets held on the account. In line with this expected outcome, Peruvian

authorities opened an investigation for extinción de dominio (the Peruvian non-conviction based confiscation law) and sent a request for international judicial cooperation to Switzerland with the aim of seizing the account for the purpose of confiscation.

Box 1: Spontaneous exchange of information

The first spontaneous transmission of information took place between Switzerland and Peru in relation to the case against Montesinos, the ex-head of intelligence of former Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori. The information about the Montesinos accounts were reported by the Swiss Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) to the Swiss Attorney General's Office, which in turn spontaneously communicated the information to Peru. This was after the fall of Fujimori's regime in 2000.

The spontaneous transmission of the information to Peru allowed the Peruvian authorities to open an investigation. Subsequently, Switzerland was able to request information and evidence from the Peruvian authorities for its own investigations.

This example illustrates the value of spontaneous transmission of information, as promoted by key guidance documents on asset recovery. 11 Investigations in both States are mutually enriched, increasing the chances of successful criminal prosecution and asset recovery through close cooperation between requesting and requested States.

4 Extinction of ownership

The financial information relating to the account was sent to Peru at a time when the criminal proceedings against Evans in Peru had already long been concluded. As a consequence, the information received from Switzerland on the Evans account was referred to the specialised nonconviction based asset recovery prosecutor's office, who succeeded in obtaining a confiscation order for the account by the Specialized Transitional Court on Extinción de Dominio in December 2020. 12

If Peru had not had a law - Legislative Decree 1373 13 (hereinafter extinción de dominio) that allows for confiscation through an autonomous procedure in scenarios such as the one presented in this case study, the confiscation of this account would never have been possible.

While this type of legislation is increasingly understood to be a critical tool in any country's legal arsenal to combat financial crime and recover stolen assets, the vast majority of countries have not yet adopted such legislation. 14 Corresponding provisions in the UN Convention against

Corruption are non-mandatory and hence uptake of this legal practice remains low.

The following subsections provide an overview of the relevant mechanisms and concepts of the extinción de dominio law necessary to follow the reasoning behind the case strategy (section 5).

4.1 Use cases for extinción de dominio

Experience has shown that reliance on criminal confiscation alone is not sufficient when a criminal conviction cannot be obtained, for example when the perpetrator has died, fled the country or is protected by immunity. Or even, as is the Evans case, when no court pronouncement has been made on the perpetrator's assets because they were discovered after the conclusion of the criminal proceedings. This situation is by no means uncommon in the context of transnational crime, where domestic proceedings depend on the ability of banks to track down illicit assets and to communicate their existence to law enforcement authorities in an effective and timely manner.

In a scenario such as that of the Evans case, the extinción de dominio allows for the confiscation of assets insofar as it is directed against the asset independently of the prior conviction of the asset holder. The extinción de dominio action is autonomous, which means that it is not linked or subordinated to a civil, criminal or other procedure. Its basis is essentially civil, since it is based on the principle that unlawful activities cannot give rise to a legitimate claim to property. 15

The close relationship between extinción de dominio and criminal proceedings is complex and still to be defined by jurisprudence in Peru. What seems clear, though, is that previous criminal proceedings against the asset holder relating to the same set of facts do not prevent the use of extinción de dominio. According to a well-accepted doctrine imported from common law, the mere existence of an illicit asset is a danger to the public order and creates distortions, 16 the legal status of which is for the State to determine.

In order to ensure that a case complies with the constitutional prohibition of double prosecution ( ne bis in idem ), extinción de dominio is only possible when the legal status of the asset has not been debated during the criminal trial. Otherwise, the decision against the asset holder benefits from the principle of res judicata and the disputed facts cannot, in principle, be debated in other proceedings, whether civil, administrative or criminal.

Civil law countries offer different alternatives for dealing with a scenario similar to the Evans case. Swiss jurisprudence, for example, provides a solution equivalent to extinción de dominio, as it allows for the non-conviction based confiscation of assets discovered after the trial insofar as their legal status was not debated in the previous criminal proceedings. 17

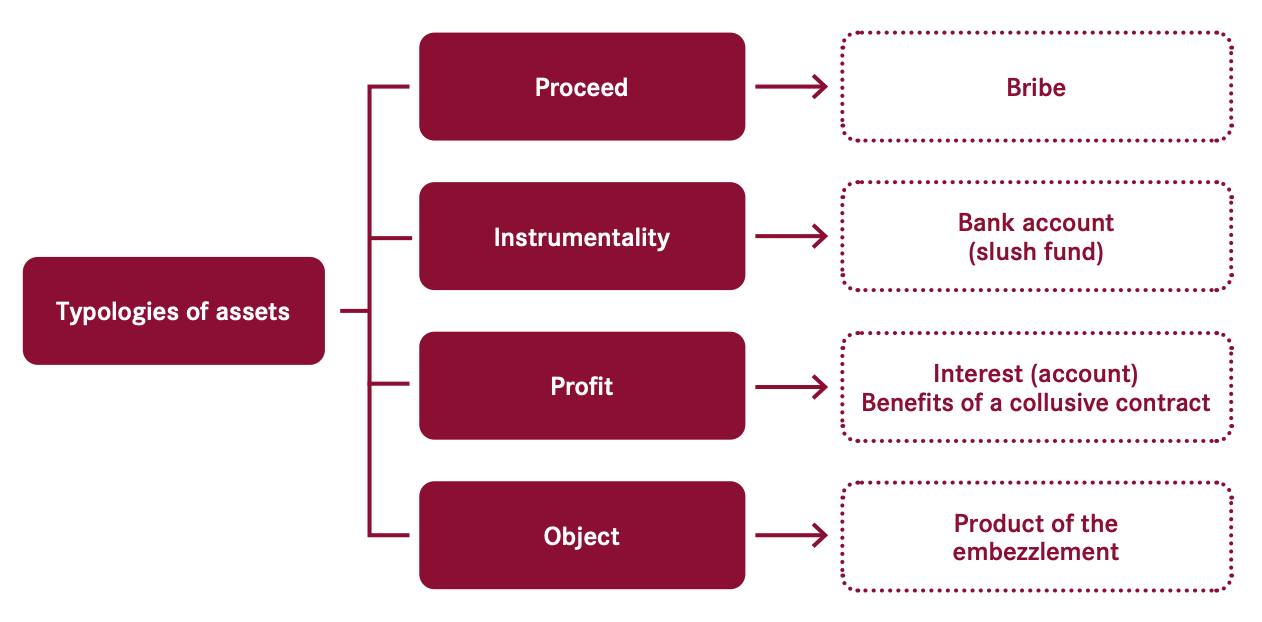

4.2 Typologies of assets

A successful asset recovery strategy requires a sound evaluation of the type of asset one is dealing with. In this case it means, among other things, determining the legal category of the asset subject to extinción de dominio.

Extinción de dominio allows the non-conviction based confiscation of objects, proceeds, profits and instrumentalities of crimes. Conceptually, it is said that the proceeds 18 and profits 19 are directly generated by the crime, unlike the instrumentalities which are the assets used to commit it (facilitation theory 20 ). The instrumentalities of crimes may in principle be licit.

The legal strategy for asset recovery differs considerably depending on whether we are dealing with one or the other. The confiscation of proceeds and profits requires the determination of a causal nexus with a previous crime (the asset is the consequence of the crime 21 ) while instrumentalities require proof of their involvement in the crime. Alternatively, their 'objective dangerousness' needs to be ascertained, i.e. the prosecuting authority is required to demonstrate that if the instrumentality is not neutralised through confiscation it will be imminently used to commit a crime. 22

Objects, for example a wallet stolen in the crime of robbery, can also be recovered under extinción de dominio because they constitute the material object of the crime. In principle, the objects of the crime are returned to their owner - who is generally the victim - because his or her property rights take precedence over the State's prerogative to confiscate the assets. 23

Fig. 1: Assets subject to extinción de dominio (e.g. corruption) According to Article 17.1.b, 24 for an extinción de dominio request to be admitted, a key precondition is that it identifies, describes and estimates the asset under dispute. The request must also establish its causal nexus with the underlying crime, which in general provides the factual background to determine the typology(ies) of assets subject to confiscation.

4.3 Conditions for applicability

The extinción de dominio law applies insofar as the specialised prosecutor successfully establishes the link between the following three elements (Art. 14.1.d):

- The Presupuesto 25

- The (allegedly) illicit asset

- The crime

According to Article 14 of the extinción de dominio law, it falls on the specialised prosecutor to collect evidence or circumstantial evidence that allows the link between the above elements to be demonstrated.

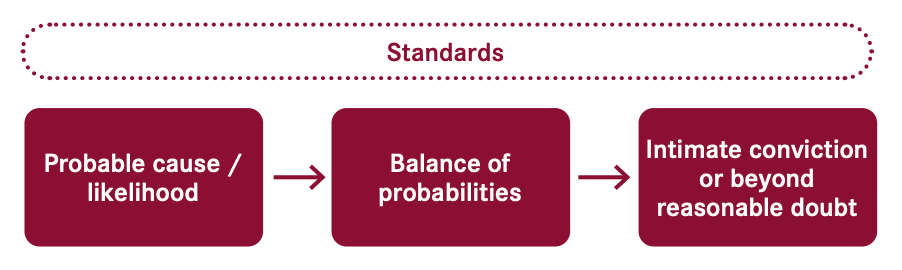

4.4 Standard and burden of the proof

The standard of proof refers to the degree of probability to which a factual proposition in a case

must be proven in order for the judge to hold it as being true. 26 The burden of proof, on the other hand, refers to the determination as to which party holds the responsibility to bring forth evidence to prove a factual proposition to the required standard.

Demonstrating the link between the asset and a previous crime can rapidly become a difficult task. This is particularly true when complex money laundering schemes are involved and assets have been moved abroad, making it necessary to gather intelligence and information from other jurisdictions, for example through mutual legal assistance (MLA). In response to this, the Peruvian non-conviction based confiscation law introduces two legal innovations vis-à-vis criminal confiscation that greatly facilitate the task of the prosecution: civil standards and the partial reallocation of the burden of the proof.

In addition to its autonomy, one of the ground-breaking features of extinción de dominio is that it applies, to a law enforcement tool, the balance of probabilities standard of proof commonly used in civil proceedings. The degree of certainty required by the judge to hold the prosecution arguments as proved is therefore lower than in criminal proceedings. The balance of probabilities standard of proof requires the judge to accept the prosecutor's arguments as proved if he or she is able to show that a particular fact or event (in relation to the asset) was more likely than not to have occurred.

Against this backdrop, during the 'financial inquiry' 27 phase, i.e. the investigative phase of the extinción de dominio preliminary proceedings, the prosecutor is requested by the law to collect evidence to prove the unlawful origin or destination of the assets. Once this phase has been concluded, the case is formally filed before the judge, who is required by law to carefully consider the request and determine its admissibility (Article 18: qualification of the request). The use of the balance of probabilities standard of proof concerns this particular procedural step where the judge evaluates the evidence.

If the evidence provided by the prosecutor is deemed sufficient, then the assets are presumed to be of unlawful origin. As a consequence, the judge calls the asset holder 28 to the extinción de dominio trial to defend his or her property rights. This particular mechanism introduces an innovative trait of the extinción de dominio: in addition to lowering the standard of proof, it provides for a partial reallocation of the burden of the proof.

Extinción de dominio therefore simplifies two key elements of confiscation law, by lowering the standard of proof the judge uses to appraise the evidence and by partially reallocating the burden of proof. As mentioned above, the obligation to establish the presupuestos (see 4.3 and footnote 25 above) falls on the prosecution during the investigative phase. The successful outcome of which leads to the presumption concerning the unlawful origin or destination of the assets, which the asset holder can rebut by providing evidence (in a balance of probabilities standard of proof) that

his or her assets have a legal origin or destination. 29

Extinción de dominio does not entail a full reversal of the burden of the proof. It operates on the contrary as a sophisticated mechanism also known in both common and civil law countries. 30 In order to maintain a balance regarding the various rights at stake, the extinción de dominio law grants numerous procedural rights to the asset holder. In particular, he or she must be put in a position to effectively defend his or her property rights before an impartial and independent judge (see below 4.5).

Fig 3: Onus of the proof

It is the responsibility of the public prosecutor to provide evidence or circumstantial evidence of the illicit origin or destination of the asset. Once the confiscation request has been admitted, it is up to the person affected to prove the lawful origin or destination of the asset (Art. 2.9).

4.5 Due process and fundamental rights

The Peruvian extinción de dominio law guarantees due process as well as other fundamental rights without restriction. These are, in fact, essential principles of this legal action. 31

The elements pertaining to the concept of due process, however, are different depending on whether the procedure is in criminal proceedings or in extinción de domino. Due process requirements developed in the context of criminal law, such as the presumption of innocence, are not applicable in autonomous legal actions against assets (in rem) principally because these legal tools do not rule on the criminal liability of the defendant nor is his or her personal liberty at stake. As a consequence, due process requirements are modulated in extinción de dominio, which replaces in this regard the notion of culpability (guilt) of an individual with the concept of 'illicitness' applicable to assets. In other words, while the purpose of the criminal trial is to find evidence aimed at proving the personal responsibility of the defendant, the extinción de dominio proceedings aim to discover whether or not the concerned assets are of illicit origin or destination.

Extinción de dominio is a form of non-conviction based confiscation whose purpose is to retrieve illicit assets generated by the most serious forms of crime (Article 1). It is in that context a reparative

measure rather than a penalty or punishment. 32 This bears particular importance in relation to the calibration of the due process requirements applicable to the extinción de dominio trial. Civil standards of proof are applicable insofar as the legal action is considered reparative. This is in contrast to if it were to be deemed a penalty or punishment, in which case the higher standard of proof, namely proof beyond reasonable doubt which is used in criminal trials, would apply.

As discussed, extinción de dominio applies the balance of probabilities standard of proof 33 commonly used in civil proceedings. The procedural mechanisms that extinción de dominio deploys are, however, not exactly those of civil proceedings. This is because civil proceedings decide on the legal relationships between individuals, while extinción de dominio proceedings have the State as the claimant. This leads to an important asymmetry in the balance of power between parties to the proceedings, as a consequence of which the asset holder under extinción de dominio is granted all crucial procedural rights, including the right to a fair trial, the right to examine the case file, the right to be heard and to provide evidence, and the right to a reasoned and legally based court decision (Article 5). In addition, Perú has established a specialised two-tier judicial system to ensure compliance with the right to obtain a judicial review of the decision.

Numerous countries in Europe know nowadays such models of confiscation in their domestic legal frameworks. Likewise, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) 34 reiterated jurisprudence has confirmed both the applicability of the civil standard of proof to reparative actions and the compliance of such confiscation models with the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). 35

Box 2: ECtHR and non-conviction based confiscation

The ECtHR has held that non-conviction based confiscation actions are non-punitive, wherefore the application of civil standards complies with the human rights standards under the ECHR. Particularly the following statements by the Court should be noted: 36

The Court observes that common European and even universal legal standards can be said to exist which encourage, the confiscation of property linked to serious criminal offences such as corruption, money laundering, drug offences and so on, without the prior existence of a criminal conviction.

The Court reiterates its well-established case-law to the effect that proceedings for confiscation such as the civil proceedings in rem in the present case, which do not stem from a criminal conviction or sentencing proceedings and thus do not qualify as a penalty but rather represent a measure of control of the use of property within the meaning of Article 1 of Protocol N°1 [European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)] cannot amount to the 'determination of a criminal charge' within the meaning of Article 6 § 1 of the Convention and should be examined under the 'civil' head of that provision.

In addition to due process, extinción de dominio impacts the right to property as it imposes on the owner the use of his or her property in accordance with the social interest as defined in the

Constitution 37 and the caselaw. 38 Indeed, the criminal instrumentalisation of property authorises the prosecutor to seek its confiscation in scenarios in which the property is only virtually related to a crime (illicit destination). 39

The right to property is a fundamental principle of modern democracy and it must be protected vigorously in constitutional and international instruments. The right to property is, however, not absolute. 40 Since the late 1970s, this issue has occupied the ECtHR, whose jurisprudence admits that confiscation laws impose limits on the use of property as per Article 1(2) of the additional Protocol to the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. 41

According to ECtHR caselaw, States Parties are permitted to implement laws that are deemed necessary to regulate the use of property in compliance with 'national interests'. 42 As a consequence, only signatory States are legitimately entitled to judge the necessity and limits to be imposed on such rights. The ECtHR should limit its interpretative powers to scrutinising the legality and the aim envisioned in the said restrictions. In Raimondo v. Italy, for instance, the fight against organised crime in Italy was considered a sufficient goal to justify preventive confiscation under Italian confiscation law. 43 The Phillips case, on the other hand, offered the ECtHR an opportunity to affirm that the far-reaching confiscation approaches provided for under UK law established a regulation of the use of property proportionate to the requirements of the fight against the 'scourge of drug trafficking'. 44

Case strategy

5.1 Early considerations

It rapidly became obvious that the Evans account could not be considered the proceeds of crime given the difficulties in tracing the assets back to a (previous) crime. The Swiss investigation was able to establish that the assets in the Evans account were transferred from an account at the First Interstate International Bank in the United States; however, further information on the transmitting

account was missing in the Peruvian investigation. Given the time that had elapsed since the account was opened (1991) and the time limits on due diligence obligations in the financial system, it appeared unlikely that more precise data would be obtained 30 years later.

In the same vein, nor could the Evans account be considered an instrumentality, as this would require demonstrating its involvement in a crime or else its dangerousness as per the discussion in 4.2 above. When the instrumentality is a bank account investigated for its links with a terrorist organisation, it is necessary to provide evidence that the assets it contains were, or will imminently be, used to finance terrorist activities. Neither of these conditions were satisfied in the Evans case. Indeed, although the Shining Path theoretically had access to the Evans account (granted by the power of attorney provided by Evans) it was never proven that the terrorist organisation had actually accessed the account. Likewise, it seems difficult to argue that a 30-year-old account, currently restrained under both the Swiss and the Peruvian investigations, could 'objectively' be considered dangerous.

However, extinción de dominio allows the confiscation of assets for reasons related to their illegal (future) use or destination (Art. 1). By doing so, it permits the forfeiture 45 of assets not only because they arise from an illicit source but also because their purpose is illicit. This criminal policy consideration is common in legal frameworks for confiscation. For example, under Swiss law, '[t] he court shall order the forfeiture of assets that have been acquired through the commission of an offence or that are intended to be used in the commission of an offence […]'. 46

The notion of illicit purpose partially overlaps with the notion of instrumentality to the extent that in both cases an asset (the Evans account) can potentially be used to commit a crime. What is decisive in extinción de dominio, however, is to demonstrate that the asset had an illicit purpose. In the Evans case, the evidence provided by the prosecution clearly proves beyond any doubt that the assets were intended to finance acts of terrorist violence by Shining Path (see below 5.2). 47

Box 3: Slush funds

Although there are many differences, the facts underlying the Evans account as regards the identification of its origins are reminiscent of the difficulties associated with the recovery of assets from so-called slush funds.

Slush funds are accounts that contain assets 'diverted' from a company's regular accounting systems using fraud and money laundering methods. The assets come, in a large number of cases, from a company's legal sources and are accumulated to bribe officials without being (yet) used for specific crimes. They are deposits of funds that will potentially be used in the commission of future, as yet undefined, crimes.

Early experiences in German and Swiss case law have identified conceptual problems in confiscating these accounts because of their lack of close connection to a specific crime. 48 In the Siemens case, for example, the identified slush funds were not confiscated as instrumentalities because no connection to a specific crime could be proven. Indeed, German confiscation rules require an offence to have at least been initiated to authorise the confiscation of any implicated asset. 49 The accounts were eventually confiscated for equivalent value in the context of out-ofcourt settlements. 50

5.2 Strategic centrepiece: the Evans account as the object of crime

The prosecutor's case strategy considered the Evans account as the object of the crime of terrorist financing. 51 Article 7.1.a of the extinción de dominio law allows for the confiscation of assets that are the 'material objects' of crime 52 (see section 4.2 above). 53 This is, the property that is (materially) affected by the crime.

The legal category of object is simple to comprehend when we refer to (corporal) assets, for example, in crimes against property. In the crime of theft, the stolen property is the object of the crime. This category becomes more elusive when we refer to abstract crimes such as money laundering or terrorist financing. In the money laundering offence, for instance, it is acknowledged that the material object is the proceeds of the previous crime but also its surrogates (e.g. financial instruments) traceable to the crime. 54 Based on this, the prosecutor's strategy strives for a broader interpretation of the concept of object of crime in the context of extinción de dominio and to incorporate immaterial property rights (financial portfolios, cryptocurrencies and other derivatives) insofar as they are the property 'affected' by the criminal behaviour.

In relation to the above, Peruvian jurisprudence 55 and doctrine 56 consider assets, in any form, intended to finance acts of terrorism as the material object of the offence of terrorist financing. 57 In the Evans case, the assets in the account were the object of Evans' criminal activity of gathering

- 52 The 'material object' is a concept of criminal law used in civil law countries to determine the elements of the crime.

- 56 Aladino Gálvez (2019), Extinción de Dominio, Nulidad de actos jurídicos y reparación civil, 100.

and making them available to the terrorist organisation to finance its activities. 58

When objects of crime are involved in confiscation proceedings, whether civil or criminal, it is essential to determine whether there is a victim entitled to restitution. Implicitly, the consideration is whether the confiscation procedure should be paralysed because a (stronger) property right will clearly defeat the right of the State to confiscate or retain the assets, as described in Box 4 below.

Box 4: Confiscation of objects of terrorist financing

Objects represent a conceptual category of assets subject to extinción de dominio. Objects are understood to be all those assets 'on which illicit activities have fallen, fall or will fall.' 59

When the mere existence of the object constitutes a danger to public safety, its destruction is generally ordered (e.g. counterfeit goods). In the case of stolen, misappropriated or other diverted assets, the obligation is to return them to their owner. The State does not have an absolute right to confiscate the asset when a victim has a prevailing property, or equivalent, right.

At the heart of the Evans strategy is the interpretation that the objects of crime can be confiscated and retained by the State in all cases in which the crime did not cause direct and immediate harm to an individual victim, for example in crimes against collective interests such as corruption, terrorist financing or criminal organisation.

In his decision, 60 the specialised judge held that in order to determine whether or not the Evans account is the object of the crime of terrorist financing, two conditions must be satisfied:

- The determination of the crime (legality). In a further parallel with anti-money laundering statutes, extinción de dominio admits a general demonstration of the crime that generated the assets, whose existence and underlying facts must be established in a generic way. In that regard, Evans was criminally convicted for 'acts of collaboration' with terrorism, which included, according to the Peruvian Criminal Code in force at that time, making funds available to finance the criminal activity of a terrorist organisation. The criminal judgement shows that the judges accepted that Evans played a key role in the logistics and finances of Shining Path, which included the opening of bank accounts. 61 In any case, it is clear that the opening of bank accounts for the purpose of financing terrorist organisations constituted a criminal offence under Peruvian law at the time Evans opened the Swiss account.

- The linkage of the account with the crime in the sense of being its 'object' (causality). 62

The following evidence offered by the prosecutor was critical to satisfying this condition:- i. the identification of Evans - in the criminal proceedings - as a member of the Shining Path; 63

- ii. the identification of Evans as the beneficial owner of the account;

- iii. the existence of an unlimited power of disposal over the assets granted by Evans to the leadership of Shining Path;

- iv. the Know Your Customer (KYC) documents, 64 which indicate Evans as the holder of the account and the individual who authorised the powers of attorney registered in favour of the leadership of Shining Path.

5.3 International confiscation standards

With regards to confiscation, the Evans case is similar to other terrorist financing cases in which assets alleged to have served to finance terrorist organisations are seized even if it is not possible to clearly determine their origin. An example is when accounts related to terrorist acts were fed by funds transferred from accounts in uncooperative jurisdictions or those protected by strict banking secrecy laws.

In relation to the above, two international well-recognised standards deserve to be noted:

- The 2002 UN International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism, which strongly advocates for an asset recovery approach to combat terrorist financing. 65

- The International Standards on Combating Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism & Proliferation of the Financial Action Task Force (the FATF Recommendations) recommend in this regard the creation of specific criminal offences with special confiscation mechanisms.

Box 5: FATF Recommendations on terrorist financing

Recommendation 4: Confiscation and provisional measures

- 'Countries should adopt measures [...] to enable their competent authorities to freeze or seize and confiscate [...] (c) property that is the proceeds of, or used in, or intended or allocated for use in, the financing of terrorism, terrorist acts or terrorist organisations.'

- '[...] Countries should consider adopting measures that allow such proceeds or instrumentalities to be confiscated without requiring a criminal conviction (non-conviction based confiscation) [...].'

Recommendation 5: Terrorist financing offence

- 'Countries should criminalise [...] not only the financing of terrorist acts but also the financing of terrorist organisations and individual terrorists even in the absence of a link to a specific terrorist act or acts.'

Interpretative notes 5 and 6 to Recommendation 5:

- 'Terrorist financing offences should extend to any funds or other assets, whether from a legitimate or illegitimate source.'

- 'Terrorist financing offences should not require that the funds or other assets: (a) were actually used to carry out or attempt a terrorist act(s); or (b) be linked to a specific terrorist act(s).'

The extinción de dominio law provides equivalent legal solutions to those promoted in the FATF Recommendations by allowing the recovery of funds intended to finance terrorism through an independent procedure against the assets themselves (in rem) that respects due process.

5.4 Mutual legal assistance - is speciality an issue?

The Evans case originated in an act of MLA. In 2017, the Swiss authorities activated the mechanisms of MLA in criminal matters to spontaneously communicate the existence and details of the account to the Peruvian prosecutors. The transmitted information was initially transferred to the competent prosecutor for cases of terrorist financing but, as the criminal case against Evans was concluded, the account's documents were transmitted to the extinción de dominio unit to initiate actions against the account itself. In fact, since extinción de dominio targets criminal assets, the international assistance mechanisms - both during the investigation phase and the international execution of judgements - belong to the realm of international judicial cooperation in criminal matters.

A question that arose in the Evans case, and that is common in the context of extinción de dominio and other non-conviction based confiscation mechanisms, concerns whether financial information received during criminal proceedings can be used in later non-conviction based confiscation proceedings. The answer to this question is related to the interpretation of the principle of speciality in international judicial cooperation.

Box 6: Applying the speciality principle

The principle of speciality concerns the possibility of imposing restrictions or conditions on the use of information sent via MLA.

The very basic principle is that the information can only be used in the 'same proceedings' that originated the request for international cooperation. Any other use requires the consent of the State sending the information (the requested State).

Speciality in international judicial cooperation is dynamic and, as it is closely linked to the principle of sovereignty, has different interpretations according to the different States' legal principles. That said, the criteria that allows for a shared use of the information lies in the interpretation of the notion of the 'same proceedings'. This is a concept which is intended to limit the wider dissemination of the information remitted to the requesting State.

International practice has developed criteria which strive for the use of shared information in proceedings different, but still linked, to that which gave rise to international cooperation. This should be possible when the following conditions are cumulatively met:

- Material identity of concerned facts: The consent of the State that transmitted the information is not necessary when the information is used in proceedings investigating the same facts in accordance with the legal criterion of the 'material identity of the facts' developed by the case law of the ECtHR 66 and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. 67 Material identity exists when there is 'a set of facts which are inseparably linked to each other, irrespective of the legal classification given to them or the legally protected interest'. 68

- The request for information concerns an offence for which the requested State would provide international cooperation: This condition is closely linked to the principle of dual criminality, according to which a State may refuse to provide MLA on the grounds that the offence underlying the MLA request does not exist in its legal system. 69

- No specific prohibition of its use in the speciality clause: Speciality is not presumed. Therefore, the State sending the information must expressly state that the information may not be shared in any other proceedings for the reasons it deems appropriate.

As per the above, the following specificities of the Evans case should be highlighted:

- The facts under investigation are closely linked to the criminal proceedings in which the information from the Evans account was received. The extinción de dominio proceedings investigate therefore the same facts as the previous criminal proceedings, but with the emphasis on the assets. Articles 7.f and 30 of the extinción de dominio law specifically regulate this scenario.

- The underlying crime is the financing of terrorism (and therefore favourable for international judicial cooperation).

- There is no specific prohibition in the Swiss spontaneous MLA imposing limitations on the use the information transferred to Peru.

6 Final decision and its execution

On 9 January 2021, the decision issued by the specialised court in the Evans case became definitive. As there is no more possibility of appeal in the Peruvian judicial system, the decision became final and enforceable.

The decision declares the prosecutor's claims founded. It orders the confiscation of the account N° 972362 at Edmond de Rothschild S.A. bank in favour of the Peruvian State and instructs the relevant authorities to initiate MLA proceedings with Switzerland with the purpose of repatriating the assets to Peru. 70

Switzerland's legal framework is regularly labelled as sophisticated and forward-thinking with regards to the possibilities to confiscate and return illicit assets. 71 Indeed, Switzerland has a unique approach to asset recovery comprising legal tools pertaining to criminal, civil and administrative matters. 72 Likewise, a national policy has been implemented over the last 30 years whose results position the Swiss financial centre as one of the leading hubs worldwide in returning illicit assets. 73

As per the discussion above, it is important to note that Switzerland grants MLA in criminal matters in foreign non-conviction based confiscation cases, provided that the requesting State is competent to prosecute the underlying crime 74 and that the foreign procedure respects internationally recognised due process standards. 75

As mentioned above, under Swiss law, the return of illicit assets can occur in various scenarios. As a general rule, 76 it follows the execution of a foreign judgement in Switzerland through MLA, but this rule is open to several exceptions. In particular, Swiss law allows for the restitution of illicit assets even in the absence of a final and enforceable foreign confiscation order. 77 This specific Swiss procedure has been used in some high-profile cases, including former cases between Switzerland and Peru. 78

Box 7: Early restitution (Art. 74a IMAC)

According to Art. 74.a of the Federal Act on International Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters (IMAC) 79 'at the request of the competent foreign authority, objects 80 or securities seized as a precautionary measure may be handed over to it at the end of the mutual assistance procedure (Art. 80d), with a view to confiscation or restitution to the person entitled.' According to Art. 74.a.3 IMAC, the restitution 'may take place at any stage of the foreign proceedings, as a rule upon a final and enforceable decision of the requesting State.'

Jurisprudence has clarified that the requirement of a final and enforceable foreign decision can be waived at the request of the foreign authority in clear cases, 81 i.e. when the illicit nature of the assets deposited in Switzerland is manifest. 82 The illicit nature of the assets is determined following the facts of the case, the results of the Swiss investigation as well as the proceedings in the requesting State. 83 In addition, criteria such as the respect of due process in the foreign proceedings as well as adherence to the relevant UN Covenant II 84 provisions by the requesting State appear to be critical under Swiss law to operate (early) restitution procedures. 85

As a general rule, the Swiss authorities have wide discretion 86 in determining whether the conditions to initiate an early restitution procedure are met. 87

Art. 74a IMAC codifies decades of Swiss jurisprudence in asset recovery and is by far the fastest and most cost-effective way for requesting States to recover illicit assets from Switzerland. 88

Other characteristics of early restitution include:

- It can occur at any stage of the criminal proceedings in the requesting State.

- Assets are returned to be used as evidence or for the purposes of confiscation in the requesting State.

- The returned assets can be used to compensate the victims of the crime.

Another possibility to return illicit assets under Swiss law is the execution of foreign decisions (exequatur ruling) set out in Art. 94 ff. IMAC. 89 For obvious reasons, a final and enforceable foreign decision is required under these proceedings. In the context of this case study, it is important to note that the Swiss government's official guidance on MLA in criminal matters declares:

'If handover [of assets] is requested as part of the execution of a final and enforceable ruling in the requesting state, then the question of whether or not the objects or assets originate from a criminal act is deemed settled, as is that of whether the objects or assets in question must be returned or seized, except where immediately obvious that this is not the case'. 90

The Evans case seems to fulfil the above-mentioned requirements in all aspects.

The Evans case exemplifies two elements of the recent emphasis on asset recovery in Peru, which is driven and shaped by the proactivity and innovation of committed prosecutors. On the one hand, the confiscation of the account in Peru demonstrates how powerfully extinción de dominio complements the criminal prosecution regime. On the other hand, the determination of the Peruvian authorities to settle a historical injustice in this emblematic case is a sign of change and hope that is worth highlighting.

We hope that this case study will enable prosecutors, judges and also policymakers to understand some of the complex issues involved and take that knowledge forward into future cases of asset recovery.

8 Bibliography

Boucht, J., 2017. The Limits of Asset Confiscation: On the Legitimacy of Extended Appropriation of Criminal Proceeds. 1st Edition. Hart Publishing.

Cassani, U., 2009. 'La confiscation de l'argent des «potentats» : à qui incombe la preuve?'. In: La Semaine judiciaire. https:/ /archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:15967.

- D. Cassella, S., 2012. Asset Forfeiture Law in the United States. 2 nd Edition. Juris Publishing.

Gálvez, A., 2019. Extinción de Dominio, Nulidad de actos jurídicos y reparación civil. 1 er Edition. Ius Puniendi, Lima.

Pieth, M., Low, L. and Bonucci, N., eds., 2013. The OECD Convention on Bribery: A commentary. 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press.

Solórzano, O. and Mbiyavanga, S., 2020. 'La recuperación de los activos venezolanos en Suiza. In Estrategias jurídicas para la recuperación de activos venezolanos producto de la corrupción. Transparencia Venezuela.

Zimmermann, R., 2009. La Coopération judiciaire internationale en matière pénale. 3rd Edition. Staempfli.

- 1 Truth and Reconciliation Commission (2003). Final Report. Available at: http://www.cverdad.org.pe/ingles/ifinal/index.php.

- 2 Truth and Reconciliation Commission (2003). Final Report. Appendix 2: Estimated total number of victims, 13.

- 3 Truth and Reconciliation Commission (2003). Final Report: Economic consequences, 327.

- 4 Adrian Oelschlegel (2006), The final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission: A critical summary of the progress made on its recommendations, 1. Available at: https://www.corteidh.or.cr/tablas/R08047-26.pdf.

- 5 National Criminal Court (2006), 09 March 2006, File No. 212-93, 55.

- 6 National Criminal Court (2006), 54 f. (note 5).

- 7 National Criminal Court (2006), 57 (note 5).

- 8 The faceless military tribunals were tribunals of exception implemented at the time of Shining Path with the aim of prosecuting crimes of terrorism in which the identity of the magistrates was reserved. See Decreto Ley 25745 (1992), 5 May 1992, established the penalties for terrorist offenses and procedure of faceless judges.

- 9 In 2003, the Peruvian government issued several legislative decrees annulling previous criminal proceedings against members of the Shining Path, see Interamerican Court of Human Rights: ICtHR (2004), 18 November 2004, De la Cruz Flores v. Perú, para. 3.

- 10 El Comercio newspaper (1991). Available at https://elcomercio.pe/lima/judiciales/quien-es-nelly-evans-la-senderista-quehoy-es-clave-para-conocer-los-fondos-de-sendero-luminoso-en-el-extranjero-noticia/.

- 11 Lausanne Guideline No. 8 and UN General Assembly resolution 71/208 of 2016.

- 12 Specialized Transitional Court on Extinción de Dominio (2020). Judgement of 09 December 2020. File N° 25-2020-0-5401-JR-ED-01.

- 13 The extinción de dominio is the latest addition in a line of Peruvian asset recovery laws dating back to 2008. See Decreto Legislativo 1373 (2018), regarding extinción de dominio. Available at: https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/normaslegales/ decreto-legislativo-sobre-extincion-de-dominio-decreto-legislativo-n 1373-1677448-2/.

- 14 The lack of non-conviction-based confiscation procedures in many European countries has been considered a serious obstacle to the implementation of a common policy, according to the Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council of 20 November 2008, “Proceeds of Organised Crime, Ensuring that ‘crime does not pay’” (COM (2008) 766 final), 6 ff.

- 15 Decreto Legislativo 1373, Preliminary Title, art. 2.4.

- 16 Stefan D. Cassella (2012), Asset Forfeiture Law in the United States, 904,905.

- 17 Swiss Federal Tribunal Ruling (hereinafter FTR) FTR 144 IV 1, recital 5. “[L] a présente cause n’est pas assimilable à l’hypothèse dans laquelle des valeurs patrimoniales dont on ne pouvait connaître l’existence au moment du jugement sont découvertes par la suite. Il y a bien une identité d’objet avec la mesure de confiscation déjà prononcée dans le jugement du Tribunal criminel, puisqu’elle se rapporte à une seule et même source de revenus. Dans cette mesure, l’autorité de chose jugée et le principe «ne bis in idem» font obstacle à la présente procédure de confiscation indépendante ultérieure diligentée sur la base de l’art. 376 CPP” (a contrario).

- 18 Commentaries on the Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions Adopted by the Negotiating Conference on 21 November 1997. Commentary 21: “The ‘proceeds’ of bribery are the profits or other benefits derived by the briber from the transaction or other improper advantage obtained or retained through bribery.”

- 19 Under the United States forfeiture law, the term proceed includes the civil law notion of profit or benefit, i.e. the indirect advantages obtained or retained as consequence of the crime, see Stefan D. Cassella (2012), Asset Forfeiture Law in the United States 904, 905. Under Swiss law, benefits of crime can be confiscated as long as a link, even indirect (but adequate), is established between the benefits and the underlying crime, see FTR 137 IV 79, recital 3.3.

- 20 The United States Coastal Area Facility Review Act (CAFRA) Status introduces the “facilitating” dimension of the asset, referring to a broader concept under which are instrumentalities of the crime any assets that makes crime easier to commit or harder to detect, see Stefan D. Cassella (2012), Asset Forfeiture Law in the United States, 937, 942.

- 21 In Switzerland, the situation is similar: “[l]es valeurs patrimoniales confiscables se rapportent à tous les avantages économiques illicites obtenus directement ou indirectement au moyen d’une infraction”, FTR 144 IV 1, recital 4.2.2.

- 22 The concept of dangerousness was developed in the context of confiscation as a safety measure, see The OECD Convention on Bribery (2014): A commentary, 306.

- 23 The OECD Convention on Bribery: A commentary (2014), 316.

- 24 All the articles in this text which are not attributed to a specific law are those of the extinción de dominio law.

- 25 From Latin Presuppositus: pre (previous) Suppositus (hypotheses). The Presupuestos are scenarios whose surrounding facts need to be proven by the prosecution for the confiscation request to be admitted by the competent judge. The Presupuestos are factual scenarios (Art. 7.1) describing the manner in which the allegedly illicit asset is connected to a crime: i) it is the object, the proceed or the instrumentality of the crime, ii) it is unexplained and suspicion exists that it may be connected to a crime, and; iii) it is a licit assets intermingled with criminal assets (tainted assets).

- 26 Johan Boucht (2017), The Limits of Asset Confiscation: On the Legitimacy of Extended Appropriation of Criminal Proceeds, 185.

- 27 Known as “Indagación patrimonial”, see art. 12 f.

- 28 The law calls the asset holder “the Requested person” (El Requerido)

- 29 Similar mechanisms had been deemed compliant with the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), see ECtHR (2004), 30 March 2004, Radio France v. France para. 24.

- 30 Art. 72(2) of the Swiss Criminal Code (Confiscation of criminal organizations’ assets) shifts the onus of the proof by rebuttably presuming that all the assets belonging to a person who has participated in or supported a criminal organisation are within the power of disposal of the criminal enterprise.

- 31 Decreto Legislativo 1373 on the Extinción de Dominio. Preliminary Title art. 2.6 and art. 4.

- 32 Decreto Legislativo 1373, Preamble.

- 33 Specialized Transitional Court on Extinción de Dominio (2020), recital 11 (note 12).

- 34 ECHR imposes the right to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal, see art. 6(1) ECHR which applies to confiscation proceedings independently whether these are considered civil or criminal, see: ECtHR (1994), 22 February 1994, Raimondo v. Italy para. 43; ECtHR (1995), 5 May 1995, Air Canada v. United Kingdom, para. 56.

- 35 Cf. for example: ECtHR (2007), 10 July 2007, Dassa Foundation v. Liechtenstein.

- 36 ECtHR (2015), 12 May 2015, Gogitidze and others v. Georgia, para. 105, 121.

- 37 Article 70 of the Peruvian Constitution declares: “[T]he right to property is inviolable. It is guaranteed by the State. It is exercised in harmony with the common good and within the limits of the law […]”.

- 38 Specialized Transitional Court on Extinción de Dominio (2020). Judgement of 27 November 2020. File N° 159-2019-0-5401, 4 f. (Moshe Case).

- 39 See above 4.2.

- 40 See, for exemple Aida Mataga, Matija Longar, Ana Vilfan (2007), The right to property under the European Convention on Human Rights: A guide to the implementation, 12. Available at https://rm.coe.int/168007ff55. See also ICtHR (2008), 6 May 2008, Salvador Chiriboga v. Ecuador. File N° 179, para. 61.

- 41 Article 1: “Protection of property: Every natural or legal person is entitled to the peaceful enjoyment of his possessions. No one shall be deprived of his possessions except in the public interest and subject to the conditions provided for by law and by the general principles of international law. The preceding provisions shall not, however, in any way impair the right of a State to enforce such laws as it deems necessary to control the use of property in accordance with the general interest or to secure the payment of taxes or other contributions or penalties”. See also, ECtHR (2002), 27 June 2002, Butler v. United Kingdom, 12.

- 42 ECtHR (1976), 7 December 1976, Handyside v. United Kingdom, para. 62.

- 43 ECtHR (1994), 22 February 1994, Raimondo v. Italy, para. 30.

- 44 ECtHR (2001), 5 July 2001, Philips v. United Kingdom, para. 52.

- 45 The OECD Convention on Bribery: A commentary (2014), 310.

- 46 Article 71 of the Swiss Criminal Code of 21 December 1937 (Status as of 1 July 2020). Unofficial English version available at: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/54/757_781_799/en.

- 47 Even if we consider that the assets have a lawful origin, the holders’ claims would be severely limited due to the criminal intention behind the opening of the account. Generally speaking, these scenarios should lead the asset holder to forego an effective defence because of the strict conditions of good faith and, depending on the underlying facts, to avoid criminal proceedings.

- 48 See legal requirements in sections 73 and 74 of the German Criminal Code, regarding the conditions for confiscation and the confiscation of the substitute value.

- 49 The OECD Convention on Bribery: A commentary (2014), 317.

- 50 Munich I Regional Court (2007), Judgment of October 4, 2007 (Case telecommunications unit of Siemens). For more, see OECD (2011), Germany: Phase 3, Report on the application of the convention on combating bribery of foreign public officials in international business transactions, available at https://www.oecd.org/berlin/47413672.pdf.

- 51 Specialized Transitional Court on Extinción de Dominio (2020), 2 (note 12).

- 52 The “material object” is a concept of criminal law used in civil law countries to determine the elements of the crime.

- 53 See in fine art. 3.7 Decreto Legislativo 1373.

- 54 Decreto Legislativo 1106 (2018), De la lucha eficaz contra el lavado de activos y otros delitos relacionados a la minería ilegal, article 1 and 2.

- 55 Peruvian judiciary (2010), Plenary Agreement N° 3 (Acuerdo Plenario N° 3) of 16 November 2010, recital 36, 37.

- 56 Aladino Gálvez (2019), Extinción de Dominio, Nulidad de actos jurídicos y reparación civil, 100.

- 57 The situation in Switzerland is identical. Article 260quiquies of the Swiss Criminal Code (Terrorist financing) refers to “funds” which includes all monetary advantages.

- 58 See above 2.

- 59 Decreto Legislativo 1373 (2018). Preliminary Title, art. 3.7.

- 60 Specialized Transitional Court on Extinción de Dominio (2020), recital 5 f. (note 12).

- 61 Specialized Transitional Court on Extinción de Dominio (2020), recital 10.b (note 12).

- 62 See 4.2 and 5.2 above.

- 63 National Criminal Court (2006), 54 f. (note 5)

- 64 Know Your Customer (KYC) is a documentary procedure aimed at verifying the identity of bank customers in the context of anti-money laundering (AML) due diligence obligations. See Art. 3 f. of the Swiss Federal Act on Combating Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing (Anti-Money Laundering Act, AMLA) of 10 October 1997 (Status as of 18 February 2020). Available at: https://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19970427/index.html.

- 65 United Nations International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism (2002). See Article 8.2: “Each State Party shall take appropriate measures, in accordance with its domestic legal principles, for the forfeiture of funds used or allocated for the purpose of committing the offences set forth in article 2 and the proceeds derived from such offences”.

- 66 ECtHR (2009), 20 February 2009, Sergey Zolotukhin v. Russia, para. 79-82.

- 67 IACHR (1997). 17 September 1997, Loayza-Tamayo v. Perú, para 66

- 68 ECtHR (2009), 20 February 2009, Sergey Zolotukhin v. Russia, recital 36, 38.

- 69 In some scenarios, Switzerland admits the use of the information in proceedings concerning offences unknown in the Swiss legal framework, see Federal Office of Justice (2009), Mutual Assistance Unit, International Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters. Guidelines, 31; FTR 124 II 184, recital 4 (concerning the Italian law on the financing of political parties).

- 70 Specialized Transitional Court on Extinción de Dominio (2020), 12 (note 12).

- 71 Financial Action Task Force (FATF), 3rd Mutual Evaluation Report on Combating Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing, Switzerland, November 2005, n. 168.

- 72 Oscar Solorzano (2020), La recuperación de activos Venezolanos, 74-107.

- 73 More information can be found at https://www.eda.admin.ch/eda/en/home/foreign-policy/financial-centre-economy/illicitassets-pep.html.

- 74 FTR 132 II, p. 178, 187.

- 75 Federal Criminal Tribunal (2013), RR.2013.164 (Khozyainov case); FTR 133 IV, p. 40, 47; FTR 122 II, p. 140, 142

- 76 By referring to the 'general rule', the IMAC leaves room for exceptions, which were used in the Marcos and Abacha cases. See Ursula Cassani, La confiscation de l'argent des «potentats» : à qui incombe la preuve?, in La Semaine judiciaire (2009), 236.

- 77 The Swiss MLA law does not use the term criminal judgment, referring merely to a decision, which presupposes simpler forms (decisions under civil or administrative law), see Federal Office of Justice (2009), 65 (note 70).

- 78 FTR 123 II 595, recital 4 ff. (Marcos Case); FTR 131 II, p. 169, 175 (Abacha Case).

- 79 Federal Act on International Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters (Mutual Assistance Act, IMAC) of 20 March 1981 (Status as of 1 March 2019), RS. 351.1. Unofficial English version available at: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/1982/846_846_846/en.

- 80 These objects include in particular, the proceeds of crime and their replacement value, See Federal Office of Justice (2009), 65 (note 70).

- 83 FTR 131 II 169, recital 7.2 and 7.6.

- 84 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966), of 16 December 1966 entry into force 23 March 1976.

- 85 FTR 123 II, p. 595, recitals 4 and 5.

- 86 Early restitution may also be based in particular on Switzerland's interest, which is considered essential in the sense of Art. 1a IMAC, not to serve as a safe haven for dictators' illicitly acquired assets.

- 87 FTR 123 II, p. 595, recital 4e; FTR 123 II 134, recital 1.4.

- 88 Federal Office of Justice (2009), 65 (note 70).

- 89 For more details on the Swiss exequatur proceedings, see Robert Zimmerman (2009), La Coopération Judiciare Internationale en Matière Penale, 727 ff.

- 90 See Federal Office of Justice (2009), 65 (note 70).