Part 2 of the Wildlife crime – understanding risks, avenues for action learning series provides companies, policy makers, practitioners and law enforcement with information and background knowledge on crime and corruption in the exotic pet trade.

3. Pet trafficking supply chain

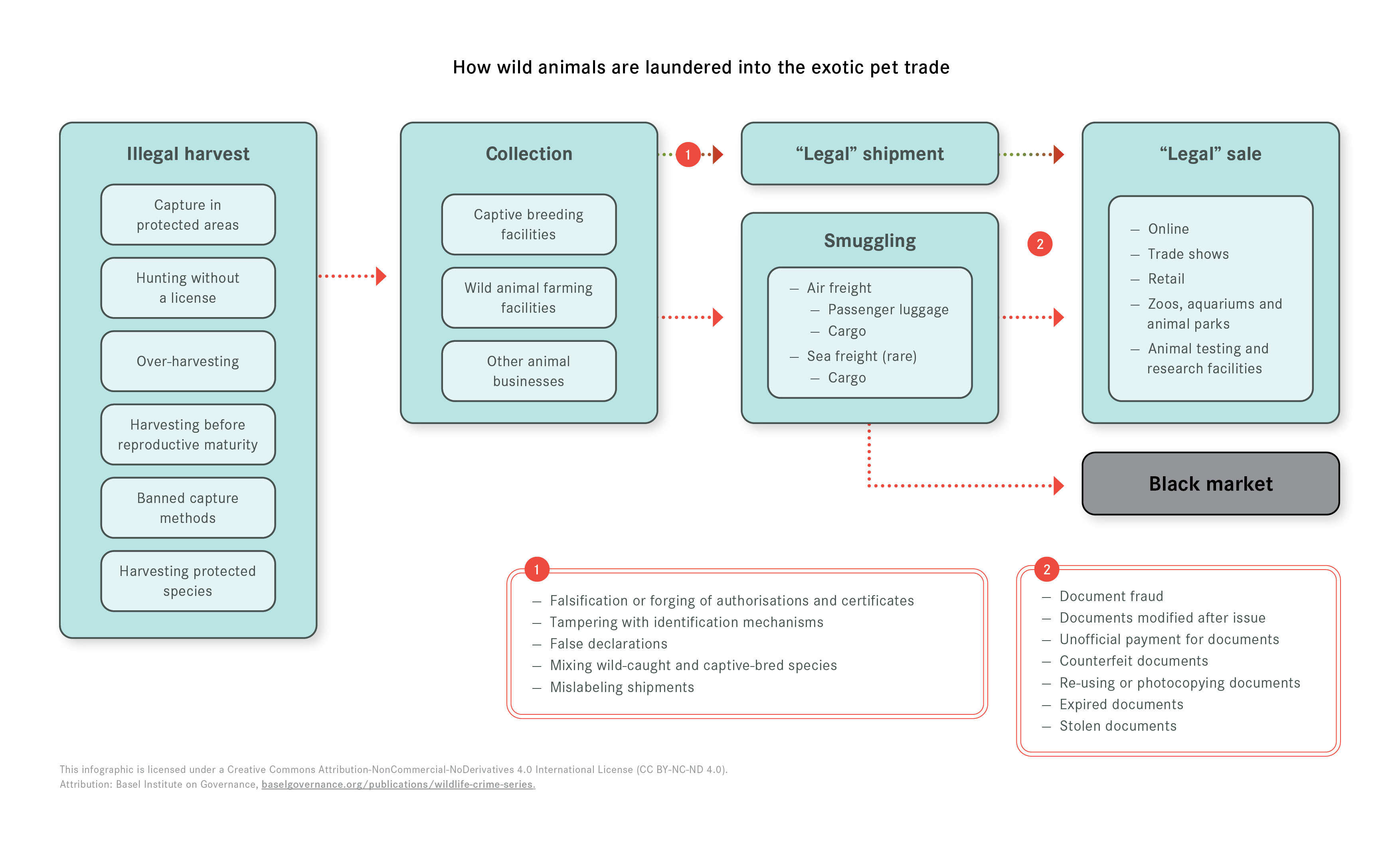

3.1. Infographic: Legal and illegal supply chains in the pet trade

The following infographic gives a simplified overview of how the legal and illegal supply chains of live pets can intertwine:

The following section describes the illegality and intermingling of supply chains in more detail.

In source locations, illegality in the capture phase involves:

capture in protected areas;Once procured, live wild animals are either laundered into a captive breeding or other live animal-based businesses, sold locally, or smuggled from their point of origin (Hall, 2019).After export – whether via smuggling or as part of a “legal” shipment – trafficked pets can often be openly sold. Repeat offenders are prevalent at every stage of the live wild animal trafficking supply chain (Crook & Van der Henst, 2020 ). Criminals working in legitimate animal-based businesses facilitate the transnational sale of live wild animals for the pet trade (and to supply zoos and aquariums) by committing document fraud, among other crimes. This includes for CITES-protected species (ENDCAP, 2012).

Traffickers subvert CITES protections in the following ways s (Crook & Van der Henst, 2020; Outhwaite, 2020):- Documents modified after issue: Information is altered to allow trade that has not been authorised.

- Unofficial payment for documents: Exporters pay more than the official price to guarantee obtaining a permit or to obtain it faster.

- Counterfeit documents: Fake permits, sometimes of very high quality, are used fraudulently to trade specimens.

- Re-using or photocopying documents: The same permit is used multiple times or duplicated.

- Expired documents: Permits are used beyond the date of expiry.

- Stolen documents: Stolen permits can be used to trade CITES-listed wildlife. Permits may be declared as lost, damaged or stolen, and the replacements used to trade wildlife. Government employees may even steal or falsely declare permits to be lost, then use or sell them.

- Mislabelling shipments: This happens in terms of both the species and the number of animals or animal parts. CITES Appendix I species that look similar to those which receive fewer protections are particularly vulnerable, as are wild-caught species certified as captive bred.

Illegalities upon imports include importing animals with falsified CITES certificates or lacking the required CITES documents entirely, and importing and trading Appendix I species for commercial purposes.

Most countries do not provide legal protections for non-native species, including CITES protected species (Chng & Eaton, 2016). Once species are trafficked into the international market they can often be freely traded online, in retail shops and through trade shows, even when sourced illegally (Hruby, 2019). Traffickers may even target species that are not protected by CITES to take advantage of loopholes in protection, and for the opportunity to work in the “legal” realm (Auliya, 2016).

Red flags associated specifically with CITES Appendix I exports are:

- CITES import permits issued after or on the same date as a CITES export permit.

- CITES import permits not signed or dated.

- CITES permits not endorsed/cleared/stamped at ports of export.

- CITES permits issued for a specific number or type of animals in the shipment does not match the number or type within the shipment.

- Documents lack the ages of exported animals.

- Exporting facilities listed are not registered with CITES.

- Exporting facilities are exporting animals they are not registered to breed or trade.