The Russian arms dealer case

The Russian arms dealer case

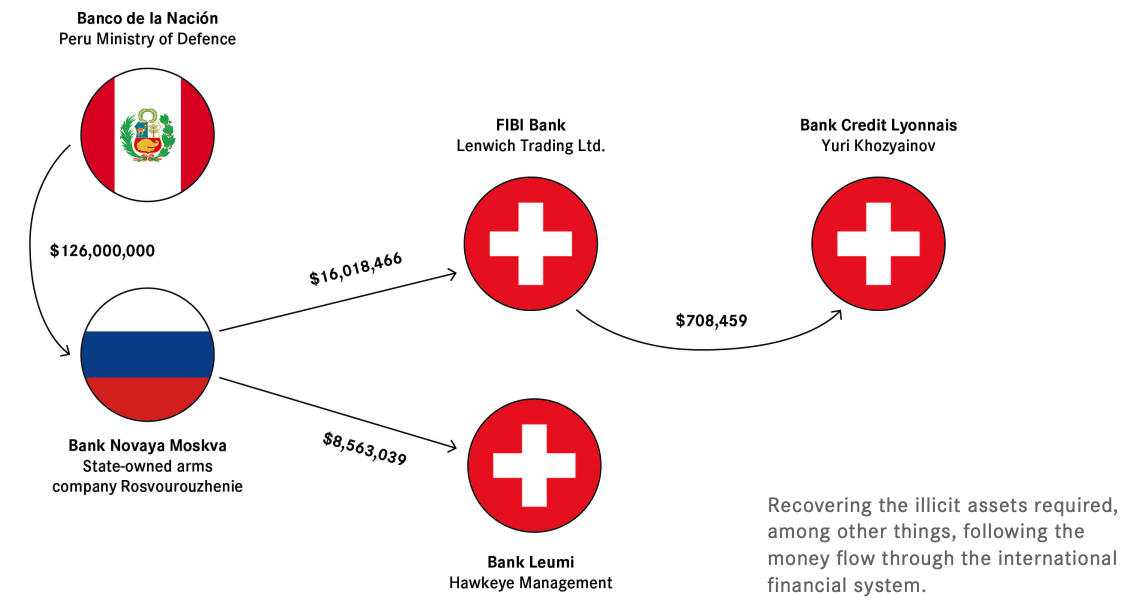

This case study explores how the Peruvian State successfully used its non-conviction based forfeiture law, extinción de dominio, to recover approximately USD 700,000 in illicit kickbacks held in a Swiss bank account linked to the purchase of military aircraft from a Russian state-owned company during Peru’s 1998 conflict with Ecuador. The funds, traced to Vladimiro Montesinos, the former intelligence chief under President Alberto Fujimori, were part of a broader scheme involving over USD 16 million in corrupt commissions. Peruvian prosecutors collaborated closely with Swiss authorities through mutual legal assistance (MLA), relying on detailed financial investigations to establish a clear paper trail connecting the funds to acts of corruption. Despite legal appeals from Yuri Khozyainov, a Russian arms dealer involved in the scheme, Swiss courts ultimately upheld the freezing and transfer of the funds.

This landmark case marked Peru’s first successful international recovery using its extinción de dominio framework and set a precedent for future cooperation with Switzerland. It highlights the effectiveness of preparatory coordination between jurisdictions and the crucial role of financial investigations in asset recovery. The case not only demonstrated that non-conviction based confiscation can respect the rule of law and human rights, but also showcased how legal systems with different traditions can align in the pursuit of justice. It offers a strong example of how coordinated international efforts and modern asset recovery laws can challenge impunity and return stolen funds to victim states.

章节大纲

-

December 2020

The Russian arms dealer case

How the Peruvian State used its non-conviction based forfeiture law, extinción de dominio, to recover a Swiss bank account containing illicit kickbacks paid for the purchase of war planes.

Key points

- → The Peruvian State used a non-conviction based forfeiture mechanism to recover a bank account frozen in Switzerland. The account contained illicit commissions paid in the context of the purchase of war planes by the Peruvian Government during the armed conflict with Ecuador.

- → This case was the first of a series of cases between Peru and Switzerland involving Peru's extinción de dominio law, which enables the confiscation of illicit assets in cases where a criminal conviction of an individual is not possible. It has paved the way for other proceedings, some of which are still pending in the tribunals.

- → The case is relatively small in monetary terms - around USD 700,000 plus interest - but hugely significant in terms of asset recovery efforts and international co-operation.

- → The case study shows how the extinción de dominio law was applied with proportionality and in full respect of the rule of law and fundamental human rights.

- → All of the facts described below are contained in the relevant and publicly available Swiss and Peruvian jurisprudence.

The case

- Vladimiro Montesinos Torres was the chief of the Peruvian intelligence service and advisor of former Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori (in office from 1990 to 2000). Montesinos headed a criminal organisation through which he systemically distributed bribes to public officials to accumulate influence over vast areas of government, the media and public life in Peru.

- Fujimori and Montesinos orchestrated large procurements for the Peruvian State that were tainted with corruption and resulted in massive losses for Peru. Together with their enablers, they stole several billions of US dollars in public assets from Peruvian coffers.

- In 1998, Montesinos and Fujimori instigated the purchase of military aircraft by the Peruvian state. The vendor was a Russian state-owned company by the name of Rosvooruzhenie, whose vice-director was a Russian citizen called Yuri Khozyainov.

- Montesinos and his allies received illicit commissions totalling more than USD 16 million in relation to a single procurement contract. These commissions were paid into two Swiss bank accounts at First International Bank of Israel (FIBI) and Bank Leumi in Zurich. This scheme, as well as later acts of money laundering, were detected and subsequently investigated in several jurisdictions, including Peru, Switzerland and Luxembourg.

- It was later revealed that Khozyainov was deeply implicated in Montesinos' money laundering scheme. Of the USD 16 million in illicit commissions, around USD 708,000 were forwarded to an account held by Khozyainov at the bank Credit Lyonnais.

- The bank reported Khozyainov's account to the Swiss Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) and it was subsequently frozen as part of a Swiss money laundering investigation. A few years later, Peru also investigated the case, applying non-conviction based confiscation techniques. It requested and exchanged evidence with Switzerland through the formal channels of mutual legal assistance (MLA).

- Khozyainov appealed the seizure of the assets in Switzerland, claiming Peru did not grant him a due process and that the freeze violated the Swiss MLA regulations. In February 2014, the Swiss Federal Court rejected Khozyainov's appeal and upheld the freezing order (Decision RR.2013.164).

- In February 2016, the Peruvian courts ordered the confiscation of Khozyainov's Swiss bank account.

- Two months later, Peru requested Switzerland to execute the decision and to hand over the assets, including interest.

- Switzerland granted MLA and executed the request in June of that year, but Khozyainov appealed to the Swiss Federal Criminal Court. The court rejected his arguments and ordered the return of the frozen assets to Peru (Decision RR.2016.147).

- Arguing a further violation of rights of constitutional nature, Khozyainov lodged an appeal at the Swiss Federal Supreme Court, which ultimately ruled that that the Peruvian investigation and trial was fair in all aspects.

What can we learn from this case?

The value of early preparatory meetings

Among the many lessons learned in this process was the great importance of preparatory meetings between central and executing authorities.

It is continuously pointed out in international fora that for an asset recovery case to be successful it needs to be closely coordinated between requesting and requested States. We profoundly adhere to this statement.

In practice this means that substantive work needs to be undertaken as a basis for such discussion and coordination. The case examined here has provided Peru and Switzerland with the opportunity to discuss in detail the mechanisms Switzerland will use to recognise and execute the Peruvian decision based on a typology of confiscation which is unknown in the Swiss legal framework.

On the other hand, these preliminary meetings allowed the Peruvian authorities to understand the conditions in the Swiss domestic legal framework for the execution of foreign confiscation orders.

Creating precedent-setting jurisprudence

Obviously, the above-mentioned exercise requires innovative thinking and a deep knowledge of both legal systems as well as the languages and legal traditions. ICAR's specialists, in close coordination with prosecutors of the requesting and requested state, supported these efforts.

The end conclusion was that both legal systems had equivalent provisions for dealing with similar underlying facts. This enabled the Peruvian decision to be admitted in Switzerland for execution.

Financial investigations at the heart of asset recovery

Independently of the underlying legal action that led to the recovery of the illicit assets, Switzerland's capacity to cooperate in such asset recovery scenarios depends on two main preconditions pertaining to the foreign procedure:

- The respect of due process requirements in the victim State.

- That the asset is of criminal origin, i.e. is linked to a crime. This is necessary in order to execute the foreign decision through MLA in criminal matters.

It is no simple matter to demonstrate in court that assets - especially when they undergo several transformations in a money laundering scheme - are the proceeds of a crime.

In the course of our work in Latin America, ICAR's financial investigators and their Peruvian counterparts had been able to establish with a high degree of certainty that the assets in the Swiss accounts originated in the Peruvian treasury. To do this, they needed to analyse a large amount of financial data received by Peru through MLA channels. The financial reports were able to reconstitute the paper trail and were used by the Peruvian prosecutors to satisfactorily support their claim in the domestic courts.

At the same time, the financial investigation showed without a shadow of doubt that the assets result from the corruption offence perpetrated by Montesinos and his associates.

This in turn provided the legal argument that the Swiss authorities needed to cooperate in criminal matters, even if the underlying foreign confiscation order did not result from ordinary criminal proceedings but from a non-conviction based forfeiture action.

Learn more

- Read an interview with Peruvian prosecutor Dr Hamilton Castro on the challenges of applying the extinción de dominio law in international cases.

- A comprehensive description of all historic cases using Peru's extinción de dominio law can be found in the 1,100-page Compendium of Jurisprudence on Extinción de Dominio published in July by Peru's Procuraduría General del Estado (in Spanish).

- Learn more about how the Basel Institute, through its International Centre for Asset Recovery ( ICAR ), provides assistance to victim countries in recovering assets stolen through corruption. In addition to this type of technical assistance on specific asset recovery cases, ICAR also delivers capacity building programmes and contributes to States' efforts to introduce legislative and institutional reforms to facilitate asset recovery

Keywords

Extinción de dominio

Non-conviction based confiscation

International cooperation

Human rights

Switzerland

Peru

Montesinos

About this Case Study

This publication is part of the Basel Institute on Governance Case Study series, ISSN 2813-3900. It is licensed for sharing under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

Suggested citation: Solórzano, Oscar. 2022.

'The Russian arms dealer case.' Case Study 4, Basel Institute on Governance. Available at: baselgovernance.org/case-studies.

The Basel Institute's asset recovery work is funded primarily by the core donor group of the International Centre for Asset Recovery (ICAR): the Government of Jersey, Principality of Liechtenstein, Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad), Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO). In addition, a portion of the Basel Institute's asset recovery assistance in Peru is funded by the Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs, through the Subnational Public Finance Management Strengthening Programme (Programa GFP).

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of these institutions and governments, or of the University of Basel.