The Kiamba case: achieving a civil asset forfeiture order and criminal prosecution

The Kiamba case: achieving a civil asset forfeiture order and criminal prosecution

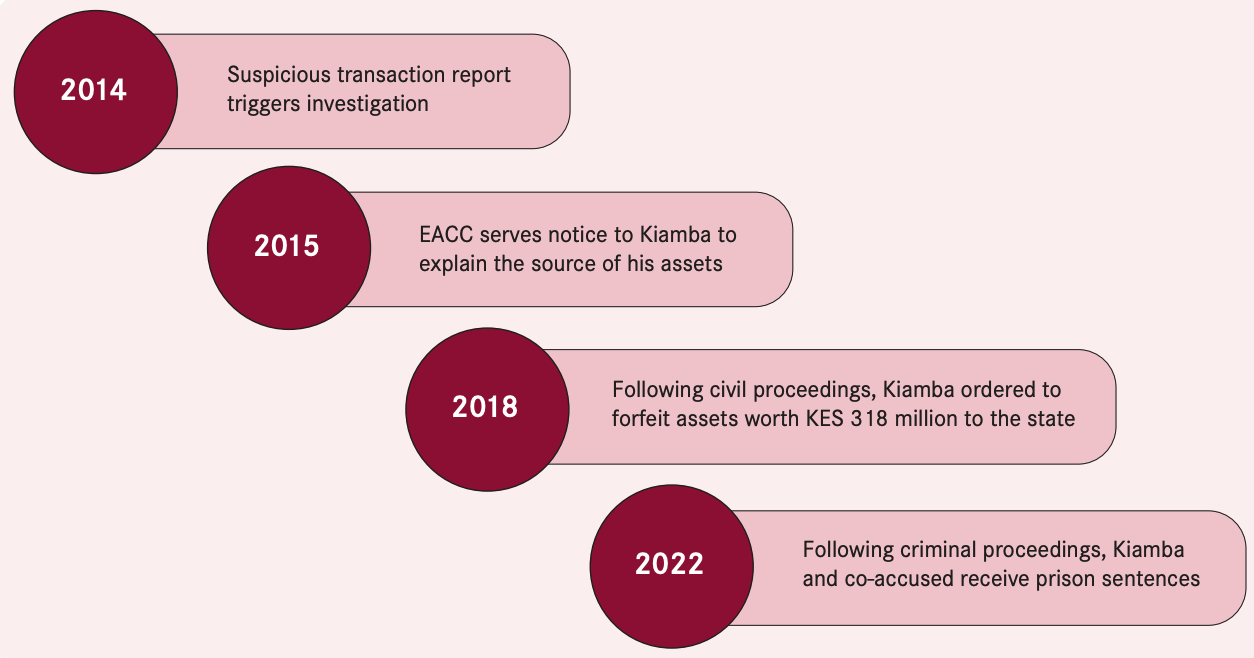

In 2014, a suspicious transaction report led Kenya’s Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) to investigate Jimmy Kiamba, then Chief Finance Officer of Nairobi County. The inquiry revealed that Kiamba, along with three others, authorized payments for non-existent office equipment, resulting in significant financial losses for the county. Under Kenya’s Anti-Corruption and Economic Crimes Act of 2003, the EACC initiated civil proceedings, culminating in a 2018 court order for Kiamba to forfeit assets worth approximately USD 3 million to the state.

Parallel criminal proceedings faced initial setbacks when the Milimani Anti-Corruption Court acquitted Kiamba and his co-conspirators. However, in July 2022, the High Court overturned these acquittals, sentencing Kiamba to a cumulative 15 years in prison for conspiring to defraud nearly USD 150,000 from City Hall. He was given the option to serve three years concurrently or pay a fine of USD 88,700 to avoid imprisonment. His co-accused received similar sentences, with varying prison terms and fines. This case exemplifies the efficacy of employing both civil and criminal proceedings to expedite asset recovery and secure convictions in corruption cases.

Section outline

-

November 2022

The Kiamba case: achieving a civil asset forfeiture order and criminal prosecution

How Kenya achieved both a civil asset forfeiture order and a criminal conviction against a former public official involved in corrupt procurement deals.

Simon Marsh , Senior Investigation Specialist and Coordinator Southern and East Africa, Basel Institute on Governance

Key points

- → The case involves Jimmy Kiamba, the former Chief Finance Officer of Nairobi County in Kenya, who conspired with three others to defraud the county government by authorising payments for phantom office equipment.

- → Following a financial investigation and civil proceedings under Kenya's Anti-Corruption and Economic Crimes Act (2003), Kiamba was ordered to forfeit around USD 3 million in assets to the state.

- → A subsequent criminal case based on the same underlying facts and investigation ultimately led to his conviction in 2022.

- → The case demonstrates how a 'belt and braces' approach - applying both civil and criminal proceedings - can help anti-corruption agencies to confiscate the proceeds of drags on or fails to reach the stricter standard of proof.

- → It also highlights the impact of providing hands-on mentoring to investigators during real ongoing cases and over an extended period of time.

The case

- A suspicious transaction report to Kenya's Financial Reporting Centre in 2014 triggered an investigation into Jimmy Kiamba, Chief Finance Officer of Nairobi County at the time. Numerous assets were frozen pending the outcomes of the investigation, including cash worth around KES 126 million (approximately USD 1.2 million).

- The investigation was led by an officer of the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) with the support of a mentor from the Basel Institute's International Centre for Asset Recovery.

- Following an extensive financial investigation, in 2015 the EACC served a notice on Kiamba to explain the source of funds used to purchase several properties in Kenya, including houses, maisonettes, apartments and plots of land.

- The order was served under Kenya's Anti-Corruption and Economic Crimes Act (2003), which allows for the recovery of unexplained assets from public officials where there is reasonable suspicion of corrupt conduct. These matters are adjudicated in the Anti-Corruption division of the High Court.

- Following the successful conclusion of civil proceedings, Kiamba was ordered to forfeit assets worth around KES 318 million (USD 3 million) to the state. 1

- Building on the financial investigation and the evidence it revealed, a criminal prosecution was launched concurrently against Jimmy Kiamba and three other public officials. The Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions charged the four with offences including abusing their public office to authorise illegal payments for office materials that were never in fact purchased.

- The Chief Magistrate of the Milimani Anti-Corruption Court initially acquitted Kiamba and his co-conspirators, but the ODPP appealed the decision.

- In July 2022, High Court Justice Esther Maina overturned the acquittal. She sentenced Jimmy Kiamba to a cumulative 15 years in prison for conspiring to defraud the City Hall of nearly 18 million Kenyan shillings (around USD 150,000). He may serve the sentences concurrently for a total of three years or pay a fine of KES 10.7 million (USD 88,700) to avoid the prison sentence.

- His co-accused, former County Secretary Lilian Ndegwa, former Senior Secretary at the Department of Finance Regina Rotich and former Head of Treasury Stephen Osiro, were similarly sentenced to cumulative prison sentences ranging from 6 to 12 years or fines from KES 1.2-9.5 million. Osiro is also subject to separate forfeiture proceedings totalling KES 293 million (approximately USD 2.5 million).

- Kiamba remains a co-accused in another ongoing case involving the former Nairobi Governor under which Kiamba served. 2 The case involves the disappearance of KES 213 million (USD 1.8 million) from the public treasury during his tenure.

What can we learn from this case?

Applying both civil and criminal proceedings

The case sets an important precedent in its use of both civil and criminal proceedings (a 'belt and braces' approach). The same underlying investigation and evidence were used to forfeit a significant amount of assets (in a civil procedure) and achieve a conviction (in a criminal procedure).

Conducting the civil case before the criminal case enabled the state to recover the assets relatively quickly, before they could be dissipated and with the result that Kiamba and his circle could not enjoy the proceeds of his crimes. Since asset forfeiture helps to remove the profit incentive to engage in corruption, achieving the forfeiture order as quickly as possible is important for the deterrent effect.

Moreover, if the prosecution had failed to reach the required strict standard of proof in the criminal case, the state would still have been able to recover the assets.

The value of the financial investigation

The financial investigation conducted in order to obtain the unexplained wealth order revealed evidence of corruption, which could then be used to help build the criminal case.

Among other things the investigation:

- Compared Kiamba's known lawful income vs. assets gained during a set period, using the source and application of funds method (see further reading list).

- Gathered evidence of cash deposits paid into various accounts by Kiamba and his junior staff.

- Created visualisations and charts showing the flow of the money between different accounts, as Kiamba attempted to obfuscate its source.

- Used the asset declaration form that Kiamba had been obliged to fill out as a Kenyan public official, adding to the proof that his assets were disproportionate to his lawful (and declared) income.

Technology can reduce investigative costs

The initial financial analysis of bank accounts was a lengthy process, including scanning paper files and manually converting PDF documents to Excel format. This required significant time and resources, delaying the investigation and both the civil and criminal cases.

Modern software and hardware to analyse complex financial data are an essential investment for anti-corruption agencies, to enable investigators to tackle more cases, more efficiently and more quickly.

Hands-on mentoring

The case demonstrates how anti-corruption investigators can build skills and experience by tackling domestic corruption cases with the support of an experienced mentor. As proactive investigations can take several years, this is a significant investment by both the government agencies and those funding and implementing the technical assistance programme. The lead investigator in this case, James Kariuki, said:

'The hands-on support I received from an expert of the International Centre for Asset Recovery was very helpful. We worked together on the case from day 1, which allowed me to enhance my skills in financial investigation and to implement them straight away in an important case in Kenya.

The experience gave me the confidence to pursue the case despite significant challenges, and helped to guide collaboration with other officers and agencies. I am now in charge of a team at the EACC and look forward to transferring these skills on to my officers as we tackle more and more complex cases of corruption and money laundering.'

In addition, many of the investigators and lawyers involved in this case had developed and honed their skills in previous forfeiture proceedings supported by ICAR case mentoring. This incremental growth in capacity of EACC officers has transformed the agency into a trailblazer in the region, with numerous asset recovery successes in the bag and many more in the pipeline.

Further reading

- Learn more about how the Basel Institute, through its International Centre for Asset Recovery (ICAR), assists countries in recovering assets stolen through corruption. In addition to this type of technical assistance on specific asset recovery cases, ICAR also provides widely acclaimed training programmes and advice on legislative and institutional reforms to facilitate asset recovery. See: baselgovernance.org/asset-recovery.

- For a short overview of Source and Application of Funds analysis and its many uses, see Quick Guide 22: Analysing a suspect's financial affairs in a corruption case, at: baselgovernance.org/ publications/quick-guide-22-analysing-suspects-financial-affairs-corruption-case.

- Learn how to conduct Source and Application of Funds analysis with a free self-paced eLearning course (with certificate), available on Basel LEARN at: learn.baselgovernance.org.

- For more on unexplained wealth legislation, see the open-access book Illicit Enrichment: A Guide to Laws Targeting Unexplained Wealth by Andrew Dornbierer, available at: illicitenrichment.baselgovernance.org. The author's Quick Guide 5: illicit enrichment covers the basics: baselgovernance. org/publications/quick-guide-5-illicit-enrichment.

Keywords

Kenya

Financial investigations

Unexplained wealth

Asset declaration form

Mentoring

About this Case Study

This publication is part of the Basel Institute on Governance Case Study series, ISSN 2813-3900. It is licensed for sharing under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 Inter¬national License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

Suggested citation: Marsh, Simon. 2022. 'The Kiamba case: achieving a civil asset forfeiture order and criminal prosecution.' Case Study 9, Basel Institute on Governance. Available at: baselgovernance.org/ case-studies.

The Basel Institute's asset recovery work is funded primarily by the core donor group of the International Centre for Asset Recovery (ICAR): the Government of Jersey, Principality of Liechtenstein, Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad), Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO).